Photographing Mind-Blowing Landscapes And Architecture In Chile

Torres del Paine National Park. Patagonia, February 2022.

It’s been 14 days, seven hours and 52 minutes since my last Calafate Sour in Patagonia.

Every day since I can feel reality slowly chipping away at the wall I’ve created trying to mentally stay in vacation mode. Trying to stay in those indescribable experiences, mind blowing colors and endless landscapes at the southern tip of South America.

I’ve seen a lot of beautiful landscapes in my travels, including over 25 of the best national parks the United States has to offer–and it’s not like they are not stunning–but Patagonia’s landscapes are on a whole new level.

And I had met my match in photographing them.

Photographing Patagonia. Read my product review on the GuraGear Camera Backpack, Kiboko 2.0 16L+

Patagonia’s landscape were above and beyond anything I had not only photographed, but had ever experienced before. With vibrant colors that I’ve never seen go together, like Lago Pehoe crystal blue water and army green shores to the blue glaciers melting into the milky grey waters of Lago Grey by the last sunset of the day, it felt so surreal to be living inside with them for a week. All I could do to process what I was seeing was take more photos and videos, hoping that someday it would all make sense and I could understand this place called Patagonia. Until then, I’ll keep using these photos to repair the bricks that protect these memories from the reality of life outside Patagonia.

Back in 2016 I meet a crazy Chilean in the community kitchen inside a place called Hillside at Frank Lloyd Wright’s summer home, Taliesin in Spring Green, Wisconsin.

Architect Jaime Inostroza,

I remember, we ate cereal together that morning, I think I might have been eating Lucky Charms (don’t tell). We talked about a bunch of things just trying to get to know each other but the majority of the conversation revolved around light. Jaime Inostroza was in the master’s program at the Frank Lloyd Wright School of Architecture at the time and I was spending a week there shooting and teaching photography workshops. We have shared that same passion of light and architecture for over six years now.

For Jaime and every masters student, their final project at the school was to design and build a shelter in the Sonoran desert behind Wright’s winter home at Taliesin West in Arizona. It was a final project that sets Wright’s School of Architecture apart from most, if not all the rest across the country and this experimental education was the one deciding factor for Jaime in choosing where to get this master’s degree in the United States. It took Jaime seven months to design the project working in both Wisconsin and Arizona and three and a half months to build his shelter. He was involved in every step of design and construction, and ninety percent of the build was done by his hands alone. That takes having to live with your design successes and shortcomings to a whole new level when you literally have to sleep within them.

By this time in 2016, I had been photographing up at Taliesin West home to the Frank Lloyd Wright Foundation for over five years, it was and still is my photography playground. It’s where I get to hone my photography skills, try out new photo techniques and where I learned to use a tilt shift lens. In a lot of ways, just like Jaime was training and learning how to be an architect there, I was training and learning how to become a photographer.

In 2017, for the first time, our two skills would finally get a chance to collaborate on a joint project. Jaime commissioned me to photograph his just completed shelter he named “Atalaya”. Atalaya, means crow nest, it is the highest point from the boat where you can see the horizon across the ocean. Jamie explains, “I was able to set out and design and construct a raised sleeping loft as tall as the nearby trees, where [the occupant] could watch the play of light and colors across the desert landscape."

After scouting the site and talking to Jaime about his design and, of course light, we decided photographing it with the sunset light would be best. The Palo Verde trees did not restrict the western light and would give the mountains behind the structure a beautiful pink and yellow glow to bring awareness to the Sonoran desert beauty the shelter was surrounded by.

After getting the images shot and edited, Jaime was happy with them and said, “Andrew, when I do my first design in Chile, I want you to come and photograph it” It was a super nice thing to say but honestly, I thought that was all it was.

Fast forward to October 21, 2021, I got this message from Jaime and my response.

Jaime: As you know by Instagram, I am doing a public project here in the south of Chile

It is the big brother of Atalaya! It is a lookout for the city of Temuco in a national park, the Ñielol Hill. The first week of November will be finished. I want you to photograph this project. On February I will on vacation at work, so I hope you have time in your schedule in February.

Me: This is awesome! What a huge honor to photograph your design. YES, I'm in!

This email was the catalyst for my three-week trip to Chile and Patagonia, seeing as much west and south of Santiago as I could and spending the last three days in the city of Temuco, Jaime’s hometown, and the location of his new design. As Jaime’s email hinted, the design I had come to photograph was similar to Atalaya in the way it looked and felt. He is calling it, “The Ñielol lookout” and its the big brother to the Atalaya Shelter. It uses a lot of the same design principles and building materials as Atalaya just much larger and more complex. I was really excited to see not only Jaime’s design but see how his architecture had developed since last photographing his design years ago. I got much more than I was expecting.

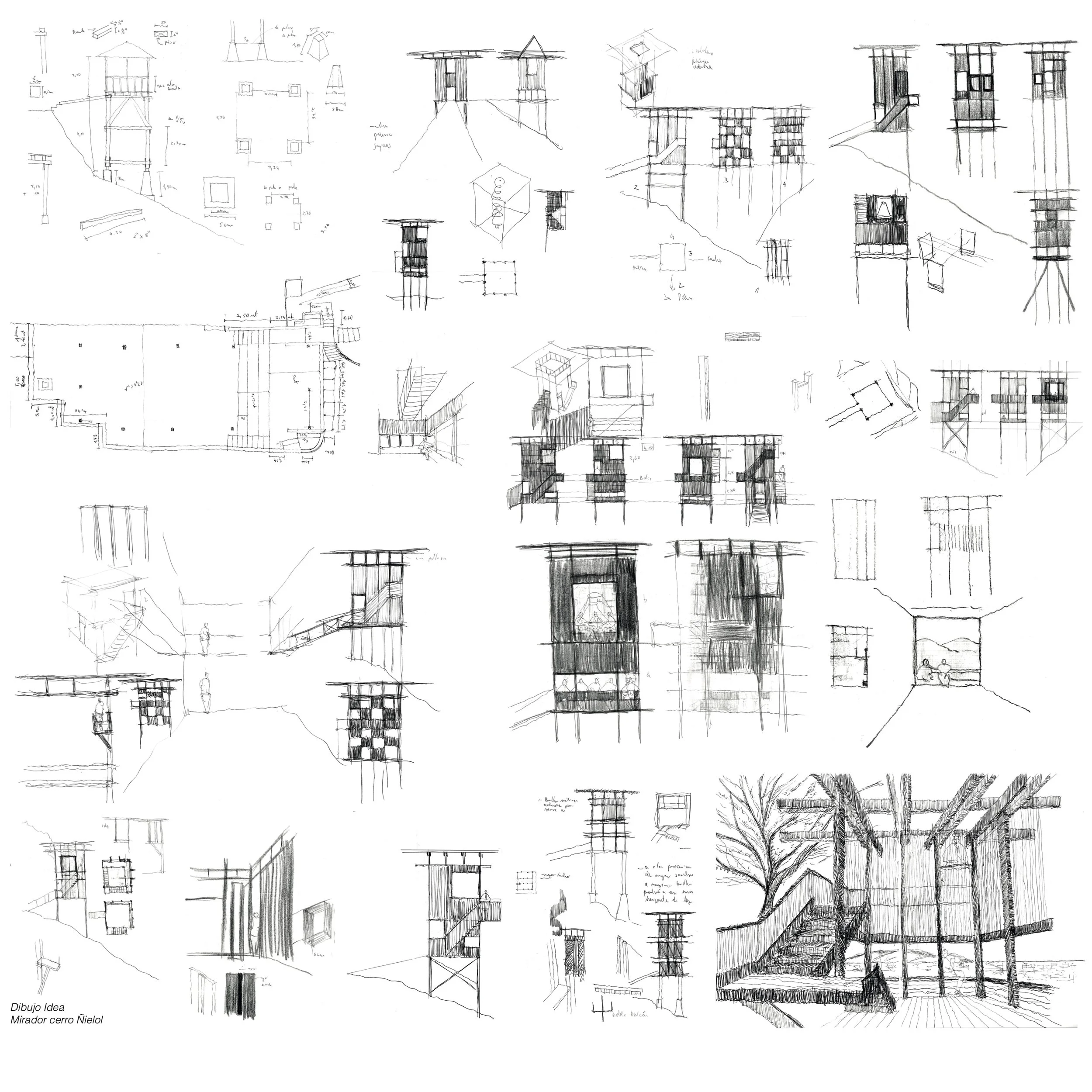

Ñielol Lookout Idea Sketches. Jaime Inostroza.

Ñielol Lookout. Jaime Inostroza.

It’s a long, narrow and windy road up through a massive thick forest of native trees, some over 100 years old to get up to Jaime’s lookout, high above the city of Temuco, home to about 300,000 people.

It only took a few seconds inside the lookout to release there was a lot more going on than a simple wooden design here, it did look and feel like Atalaya, but the lookout tower is a public space and, because of the square footage was larger and a much more thought out and functional design to spend time in. Atalaya was only designed for sleeping and to relax in. My first WOW moment was realizing that Jaime had not only designed and built his first public structure, but he had created a wonderful what I call and some in the industry call the “Arrival Sequence” of a design.

The experience of architecture can build on itself to create a sequence of moments which weave together a narrative. When successful, this narrative is much more than the sum of its parts, we call this the Arrival Sequence.

An Arrival Sequence is made up of memorable moments that create a sense of mystery and anticipation for what lies ahead. The sequence occurs from varying points from the entrance of the lookout, drawing one into the design with meaningful, visual moments both subtle and grand until you reach the terminus, in this case it would be the grand lookout view of Temuco.

This Arrival Sequence is much like a journey walking through a Frank Lloyd Wright design.

Whether you know it or not Wright is controlling you from the moment you see his design, through his front door, which are rarely in the front, and finally to how you explore the space inside. He pushes you through certain spaces leading your eye and feet with lines, ceiling height and tiny glimpses of nature around you. Visiting a Wright design is a very curated experience and most of time you don’t even know it, you just follow the flow.

That’s what I first noticed about Jaime’s space, it pushed me visually through the space. It kept me wanting to explore more and more, to walk around and see every corner and most important, it made me curious about the space and what’s ahead. The visual experience ends, ultimately, at the second level where the final full view of the beautiful city of Temuco is achieved.

Through these two videos I made while I was there you can see how Jaime’s carefully choreographed arrival sequence begins when you first see the straight and open lines of the bridge railings that leads directly towards the interior of the tower itself.

Arrival Sequence 1. The Ñielol Lookout. Jaime Inostroza.

Arrival Sequence 2. The Ñielol Lookout. Jaime Inostroza.

Your first step off the concrete to Jaime’s wooden bridge clearly denotes the transition between the already existing space to something completely different and new. When you step on the bridge, it feels different on your feet, heightening your awareness of the building materials used in the design and making a point of leaving the old world and experiencing a brand-new place and atmosphere. At this point all you see straight in front of you is tall vertical wood beams and mountains and sky framed beautifully within the structure.

As you walk forward the only view of Temuco slowly disappears on the right-hand side and the airy happy feeling of walking among the trees and fresh air quickly turn into a space that is far less inviting and open. You enter into what I call the entry portal to the main room, with wood on the left, right and above now, it’s very constricting and forces your vision forward only. It’s much like Wright’s compress and release design where he puts you in a low tight space only to open you up to the release of the larger space and view ahead. Jaime works you through this confined space to move you forward to the grand room of the tower all around you. The structure and ceiling feel like they are soaring above you while showering you with veils of beautiful strips of warm light.

With the wall of staircase to your left your eye goes two ways. One, up to diffused roof that allows light in and sight out but protects you from the elements. And two, out to the view first framed by the architecture. But after exploring, you discover it’s not the entire view, it’s only teaser. Only part of the view is shown, leaving you unsatisfied and wanting more. The curiosity of what the complete view really looks like leads you to the staircase and the second level.

In video number two, you now turn your back to the view and receive a break from the swiping vista to discover, as you walk up the stairs, that you are among the trees now, surrounded by them. It’s a wonderful moment of respect being among the trees. You, the natural world and the architecture are in balance. Each better together.

Finally, climbing up from under the tree canopy, up the last few steps you now feel like the lookout tower is rising up and finally you see the now unobstructed view of Temuco in the last of the good light.

It’s a beautiful sequence of separation from earth, through the trees and up to the sky above.